Dana Tanamachi is a designer. Accustomed to working at the behest of clients, her standard concern is delivering what it is they want to say. She’s good at it—her hand lettered chalk murals led to a surge in the style nationwide, and her work has been commissioned by everyone from Google to Starbucks to the Wall Street Journal.

So the opportunity afforded by the Laity Lodge Residency—to live onsite for a full month and create new work that expressed precisely what it was she wanted to say—represented an unprecedented challenge, both professionally and personally.

But what to “say”? The New York-based Tanamachi found her inspiration while driving across Texas after an early spring scouting visit to the Lodge. In an email at the time, she wrote, “After our discussion about themes I had another idea that I think will fit very well into the mix. I forgot how much thinking you can get done while driving the highways and backroads of Texas. It’s just not the same as riding the subway everywhere.”

That drive was a kind of homecoming. Tanamachi grew up in Houston, and her maternal grandparents, both Mexican-American, were born in South Texas agricultural towns. Migrant farm workers, each summer they criscrossed the desert Southwest picking crops.

Tanamachi’s paternal grandparents met and were married while living in a World War II-era internment camp in Arizona. When the war ended, they had no home to return to in California. A relative from the Rio Grande Valley of Texas offered refuge and the possibility of starting a new life. The Tanamachis took him up on the offer.

As quoted in the 1987 book The Japanese Texans, Dana’s grandfather, Tom Tanamachi, described their arrival in the Valley this way: “We traveled through miles and miles of desert, and all of a sudden we came into a lush garden. I liked what I saw.”

Nearly 75 years later, this story—the move from desert to garden, and the familial life that took root there—has become the conceptual and narrative focus of I Liked What I Saw, Tanamachi’s Cody Center installation. The exhibition is comprised of three groupings of works: five round works + one large landscape; a cascading series of fans; and a collection of storybooks.

Together, Tanamachi’s Lodge works tell a personal story about journeys across landscapes, both literal and figurative, and the perpetual quest for meaning along the way. Deserts (geographical, relational, spiritual, vocational) abound. And so do desert crossers—those who continue to make the hazardous journeys across these expanses. Gardens—and the hope of gardens—abound, too.

“...I’m really lucky that my grandmother would talk openly about it. But she talks from a place of forgiveness, not of bitterness.”

Dana Tanamachi

Long ago, two families lived across the road from one another on the northern shore of Japan’s Kyushu Island in Fukuoka Prefecture’s eponymously named capital city. They shared the same surname—Tanamachi—yet were only distantly related.

Many years later and half a world away, a family of Japanese Americans descended from one of the two Fukuoka Tanamachi clans was taken away from a comfortable life farming in Long Beach, California, and evacuated by train to Poston Relocation Center in southwestern Arizona, one of the largest World War II American concentration camps operated by the War Relocation Authority.

During the war, more than 120,000 Americans of Japanese heritage were detained in spartan camps spread across Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Idaho, Utah, Texas, and Wyoming.

The Tanamachi’s son, Tom, was only 19 when the war broke out. While he was interned, he attended a camp social where he met his wife, Mitsuye Nimura, and soon they were married there in the camp.

Two and a half years after the internment began, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt rescinded his order, and tens of thousands of Japanese Americans were freed. But freed to where? The Tanamachis couldn’t return to California—their farm had been turned into a government ammunition dump.

Providentially, they became connected to distant relatives who were landowning farmers in South Texas—Japanese Americans who shared the same last name and also shared whatever they had. They offered Tom’s family a spare farmhouse on their property, and a place to start over. It was not until many years later that both families would discover they were descended from the two Tanamachi families who were still living across the street from each other in Fukuoka.

“I’m fourth generation Japanese-American,” says New York designer/illustrator Dana Tanamachi.

“And I’ve always been very close with my paternal grandmother, Mitsuye. She’s still living, in Dallas, and she’s always been an influential and central figure in my life. She and her siblings, and my grandfather and his siblings and parents were all interned together there in the Arizona desert.”

Tanamachi is sitting in the living room at Laity Lodge’s Waterfall Apartment on an overcast Tuesday afternoon in May. She is reflecting on the themes beginning to emerge as she works on a body of new original pieces for her gallery exhibit, I Liked What I Saw, the culmination of her month-long artist residency here at the Lodge. Her furry canine companion, Merle, is ever present, napping near the fireplace in a shaft of sunlight.

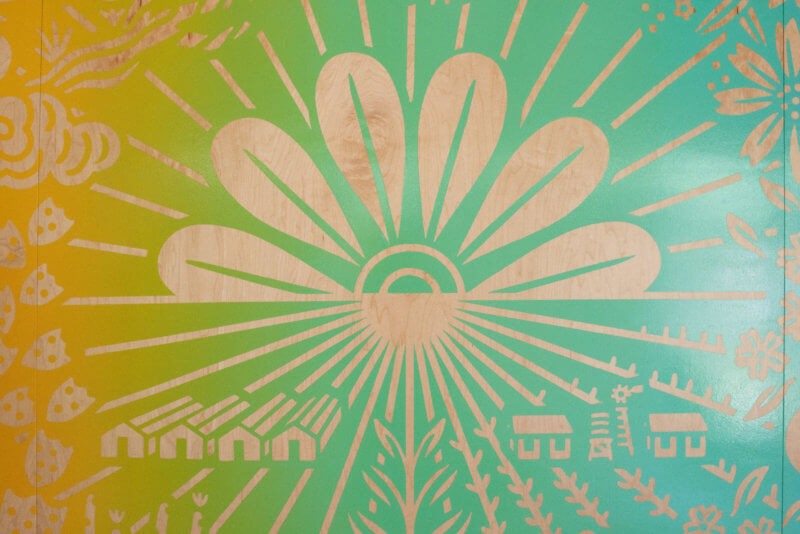

“Desert to Garden” detail depicting the transition from the Arizona camp to the Texas family farm

Her reflection is worth recounting at length:

“That internment is a huge part of my identity, and I’m really lucky that my grandmother would talk openly about it. But she talks from a place of forgiveness, not of bitterness. When they got out of camp, she and my grandfather moved to the Rio Grande Valley—those relatives gave them a new start, and we’re still very close with that side, and now I call them Aunt and Uncle, and we’ve all come full circle and are one family again.

“My grandmother became the first believer in our family. They were out on the farm, and she heard God speak to her one day in the field. She was speechless. She knew from that moment that she had to forgive the system that had imprisoned her family. So … forgiveness, not bitterness. Not that you forget about these things—we keep telling these stories so that we will not forget, so these kind of things will never happen again.

“I think that not many people in my generation whose grandparents have gone through camp have been able to openly discuss it with them, let alone through the lens of forgiveness. So I feel I have a unique insight that I’m very grateful for, and so I have wanted to tell my family’s story through some of the art here.”

The exhibit takes its name from the words of her grandfather, whose description of his family’s arrival to the Rio Grande Valley was captured by a Thomas K. Walls in The Japanese Texans: “We traveled through miles and miles of desert, and all of a sudden we came into a lush garden. I liked what I saw.”

Dana says, “I really wanted to play with that imagery of desert transitioning into a lush garden. Texas was that lush garden to him. I wanted some of the art to be a kind of love letter to Texas. I wanted to see it through the eyes of my grandfather, who found it to be so beautiful, and such a relief, and such a new beginning.”

Dana adds that her mother’s side of the family is of Mexican-American heritage. Her maternal grandparents were both born in South Texas agricultural towns—her grandfather in McAllen and her grandmother in Edna. “My mother’s family were migrant workers, and she grew up picking cotton. There were many kids, and every summer they would drive to California or to other states and pick cotton and other crops.

“So yeah, you have two very different American stories, here. The two cultures are very different, and I’m not sure that either one fully understood the other at first. There were a lot of misconceptions … but it’s still a Texan story. It’s only now really as an adult that I’ve come to appreciate the kind of mixed background that I come from and appreciate the cultural differences between the two and fully embrace them.”

[The remainder of this interview has been edited and abridged.]

How did you come into contact with the Lodge?

I got connected to the Lodge through my New York friends Chris and Janelle Domig. We’ve been close friends for a decade, and they are also longtime friends of [Laity Lodge Executive Director] Steven Purcell.

Steven came to my studio maybe five years ago. We had a lovely time chatting, and I showed him some of my work. We’d been talking since then about me coming out to the Lodge, but the timing never worked out. Then [in March], I was down in Dallas for work … and Steven asked if I could somehow get myself out here—he’d love to show me around, so I rented a car. I love driving through Texas. I had a blast just driving from Dallas to Leakey and then, when I hit the Frio River I was like, “What is this place?”

You drive through the river; it’s kind of this magical thing where you emerge out on the other side—it’s a good symbol of just being open: you don’t know what’s around the bend, you don’t know what that holds, but you keep driving and you eventually get there, and you see Gate and Steven waving at you. I finally started to understand why this place is so special. I get why people keep telling me about it. I get why people keep coming back.

How did you get a sense of what you might be able to do here as an artist-in-residence?

They took me to the Cody Center and showed me the artist studios. They told me, “You would have free reign of these spaces, whatever you can imagine, you can use whatever materials and whatever parts of the Cody Center to display the work that you want.”

My ideas started flowing, and I took a lot of pictures. When I got back in New York, I took my tablet and sketched directly on top of the photos and sent those rough sketches to Gate and Steven, and they were really excited about them. Then I just decided I’d do whatever I need to do to make it work. I’ll put my client work on hold. I’ll have an away message on my inbox for a month. I really wanted a chance to be out here and think about what I want to say and make.

Did the concept behind I Liked What I Saw emerge immediately?

When I came for that one-night visit I really had no idea what the theme of my work would be. I actually asked Steven and Gate for their ideas, because I’m in that mindset of a commercial designer where I’m usually communicating someone else’s ideas. They offered some ideas, but as we started digging deeper, more personal themes started emerging that revolved around my family, my father’s side of the family, and their Japanese-American story. And I presented them to Gate and Steven, and they loved the idea.

I do love Texas. If you’re a Texan, you’re a Texan, you know—you always will be—and I wanted the chance to spend more time here. I’m very happy with my life in New York. I love it there, and it’s hard to make it a priority to come home for more than four days in a row. So this was something that was really intriguing, to be able to spend a solid month back in this place where I’m from. I feel like I’ve fallen right back in in such a good way. I didn’t realize how much I missed it—the people and food and music and everyone, friends and family, within six hours’ drive.

Visitors to the Cody Center will see these large birch panels with intricate vinework and filigree. What has been your process to translate the digital sketch from your tablet up here at the Waterfall Apartment to a 60-inch birch circle down at the artist studio?

I start by designing on the tablet then refine them on the computer. I make stencils of the art which are cut out of an adhesive plastic material. Then once the wood has been treated and finished, I adhere the stencils to the surface. Once the whole design is adhered, I roll paint over the top.

I’ve been using One Shot lettering enamel, a very saturated, slow drying, and shiny paint which is also extremely durable. I’ve been blending different colors together to make gradients across the surface, and then once it’s dried, I peel off the stencils to reveal the wood underneath.

Watching you peel off the stencil adhesive, you’re working very slowly. It seems like a slow, contemplative type of process.

It’s a slow process, yeah. Laying the stencils down is a little stressful, registering them, getting them in the right place. If one of your stencils is off and it bumps over just a bit, then everything moves over, and it’s just a mess. I have a lot of connecting straight lines, so it’s important to get everything lined up, so I breathe more easily once the paint is off. I just have to go to bed, let it dry and in the morning I can start the peeling process, which is the most meditative part.

I don’t have to really measure. I simply remove and reveal what is underneath, so it’s the most rewarding and fun part of the process.

“You drive through the river; it’s kind of this magical thing where you emerge out on the other side—it’s a good symbol of just being open...”

Dana Tanamachi

Most people know you for your chalk murals, which had incredible national visibility a few years back. Yet it’s obvious from your recent work there’s been an intentional shift away from that style.

I got into chalk murals early on, ten years ago. It was the early days of my being in New York, and I was really young, so I had all the energy in the world, and the truth is I just really burnt out on it. I decided to stop doing chalk because it had kind of run its course. I had loved this thing and was so grateful for it, but I thought maybe it was time to see what else I’m capable of. And I’m really glad that I did.

I started incorporating illustration into the work, but didn’t feel confident in it. I never was particularly good at illustration, or maybe I just didn’t have enough practice. But I started leaning more toward that. My pieces still have such a graphic quality to them, and after a few years of that, what I do more than anything now is barely any typography and mostly illustration, so I only have just gotten comfortable with also calling myself an illustrator.

In 2016, as you were exploring this shift from typography to illustration, you took on a rather ambitious commission, the design of an illuminated Bible. The art in that book, spanning hundreds of illustrations, as well as your 2017 large scale installation in Instagram’s Menlo Park headquarters, both seem to presage the work you’ve created for I Liked What I Saw.

Yes—the ESV Illuminated Bible project came to me through Crossway Publishing, and they had interest in creating a modern-day take on a traditional illuminated Bible. This is something that would’ve taken decades for monks to do. I had eight months. (Laughs). Luckily, we have computers and drawing tablets.

We wanted it to be beautiful first of all, and something that would inspire people when they read the word. … We wanted it to be illustrative, bold—it’s just one-color illustration—yet it is intricate and ornamental. We tried to stray away from literally showing [characters], so for example, instead of showing Ruth literally gleaning wheat, I combined the image of wheat and wings and created a single image that is wings made out of wheat. That was a launching point to the work I’m creating here. It is a similar style, and you can tell it’s the same hand.

Similarly, [Instagram’s parent company] Facebook has an artist-in-residence program, and they encourage artists to do something they have never done. It was their openness to letting me do whatever I could think of that helped me come up with the stencilling technique and translate my style of illustration to a large scale. I really did learn a lot during that install and have been able to transfer so much of that learning to the residency here at Laity Lodge.

The patterns for these illustrations evoke the floral patterns from Art Nouveau, Japanese Mingei folk art, typographer-illustrator Eric Gill, and the Arts and Crafts work of Dard Hunter and William Morris. Was there a specific tradition that influenced this project more than another?

I have a lot of books about Japanese floral illustration and design, so stylistically, “Mitzi,” the piece hanging in the lobby is purposefully more in the Japanese realm. I chose different floral elements based on elements of my grandma’s story, as well as things that reminded me of her. I researched the kinds of plants that were in the Arizona desert, the New Mexico desert, the Texas desert, and then what plants are native to the Valley here, what grows in gardens there, what are the wildflowers, and what are the growing things from my dad’s memory of the farm growing up. He always told me they had a papaya tree, and I had never seen one, so included that. Their history gave me so many things to choose from.

What has the extended time in the Canyon felt like?

I’ve tried to focus my energy on creating. I have been off of the internet. I haven’t been on social media. I wanted a clean slate—I really needed to have a clear mind to tell my story. So that’s been really nice. I love seeing the hummingbirds and the cliff swallows.

Even though I live in New York City, my world’s still pretty small, so it doesn’t feel that much different to be totally honest. I work from home so it’s kind of the same setup I have here: I have my computer and my tablet, designing at a table. At home, Merle and I go on our two-mile walk every day in the city and in the park. Since I work from home, we’re together all the time. It’s special to be able to bring him here. It wouldn’t feel like normal life if I didn’t have him. He’s always a good reminder to take a break because he has to go out or go on walks—we’re really besties, and he’s my companion for life.

“I’ve tried to focus my energy on creating... I really needed to have a clear mind to tell my story.”

Dana Tanamachi

Photos by Wendi Poole and Hayden Hyde